The UK’s Shifting Immigration Policy & Public Opinion

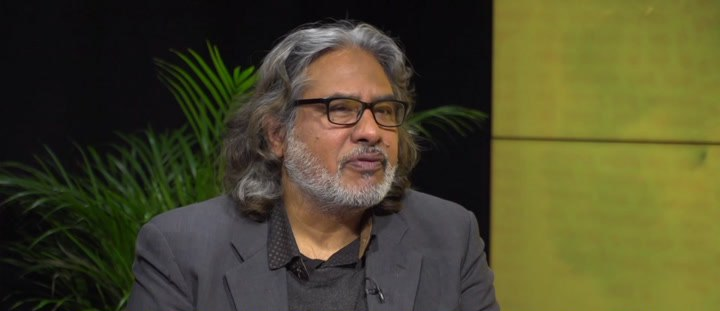

Dr Ken Fero is a filmmaker and activist based in London with Migrant Media, his new documentary film ‘Rebellion’

Dr Ken Fero is a filmmaker and activist based in London with Migrant Media, his new documentary film ‘Rebellion’ about the resistance to racism and fascism in the UK in 1980’s will be released next year. He is a Collaborative Researcher at the Global Inquires and Social Theory Research Group, Ton Duc Thang University, Vietnam.

1. What are the key changes in the UK’s immigration policy over the past year — and how are they affecting different sectors such as healthcare, hospitality, and construction?

Over the past 12–18 months the UK government has introduced a number of changes to its immigration rules and they are impacting everyone. The Home Office legislated the government’s intention to “significantly reduce” net migration and to reshape the system around higher-skill, higher-salary immigration.

This pandering to racialised fears of low skilled and migrant workers has led to a raft of restrictions including raising the minimum qualification thresholds, increasing salary thresholds and a “Immigration Salary List” but the numbers of immigrants involved in these areas are so low they are failing to meet the skills deficit from UK citizen who are emigrating abroad, perhaps to a less politically toxic country. Restrictive rules for overseas care-workers when the population is in decline and is aging is perhaps a form of societal suicide. Work visas for adult social care staff fell by about 90% in 2024 compared to 2023, following restrictions on care-worker visas.

This has left the National Health Service in a state of chaos, this falls into the hands of privateers who would want to sell off the NHS to the highest bidder, a task that even the brutal 1980’s prime minister Margaret Thatcher could not put in to the action when the UK was sold off to neo-capitalist under her regime. In hospitality and in construction significant numbers of workers, particularity in urban centres, are migrant workers (some of whom are unregistered) as well as mobile workforces from Europe, are a lifeline to the economy that Brexit has now severed.

2- To what extent are these policy shifts being driven by economic need versus political pressure from parties like Reform UK or anti-immigration segments of the electorate?

Racialised capitalism has historically been the powerhouse of the UK and, rather than racism dividing the country, it is the very cement that keeps its foundation together. Anti-immigrant sentiment is not new, indeed when Britain reached out to its colonies following World War 2 Commonwealth citizens from the Caribbean and Asia came to help rebuild the country they were met with signs that included the slogans ‘No Black, No Irish, No Dogs’ when looking for rented accommodation.

Of course those communities have settled and it is often said that they have become part of the fabric of UK society. Unfortunately that fabric has been torn most recently by the Windrush Scandal when the last government proceeded to try and deport some of the generation that had been asked to come and rebuild the country. This led to deaths and a reminder that all rights are under threat when it is in the governments political interest to do use race logic as a tool of oppression.

Surveys tell us that public concern about immigration (illegal and legal) has been rising. For example, in September 2025, 51% of Britons named immigration as an important issue, the highest since 2015 and this has been driven by a right wing trend that is sweeping Europe. Metrics like this however are more about sentiment than reality, the racialisation across the press and media and the ‘othering’ on non-white people, especially in the form of Islamophobia are the forces at play here.

Political pressure from voters concerned about immigration numbers, from parties such as Reform UK building electoral leverage has been the immediate driver of the Labour government’s policy performance. This is nothing new, throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s one of the most telling slogans that demonstrations against racism chanted was ‘Labour and Tory both the same, both play the racist game’.

3- How is public opinion on immigration evolving — is the UK becoming more closed off, or is the picture more nuanced depending on region, age, or class?

During the 1980’s the growth of the far-right led to the formation of the National Front a racist right-wing popular grouping that were advocating repatriation of the Black and Asian community. This was in an environment where racist attacks, stabbings and fire bombings were taking more and more lives. The uprisings of the 1980’s form Black and working class youth was a reaction to that fascist up swelling and the communities organised to defeat the National front. In urban centres across the UK generations of young people from the Global South are firmly ingrained in youth culture despite the racial profiling by police that continues.

The grandchildren of the National Front supporters that marched in the 1980’s are the people who are now setting fire to hotels housing asylum seekers. Racism is passed on from generation to generation unless it is met with resistance and that resistance to racism is widespread across most demographics but especially the youth who, after all, are the future.

4- Have these new immigration rules improved public trust in the government’s ability to manage borders, or are they perceived as performative?

In March 2024, 69% of people responding to an Ipsos survey said they were dissatisfied with the way the government was dealing with immigration whilst a later poll (May 2025) found that only 23% of Britons said the Labour government was doing a better job than the previous Conservative government on immigration; 42% said it was doing worse. Ipsos It is the far-right that is driving the political debate in the UK in a way in which it has not done before and indeed over the last 70 years whilst the issue of immigration has fluctuated in terms of its importance during electioneering today it is more central due to the political threat of Reform.

The recent march in London of 100,000 mostly white people was led by fascists and it was racist in nature but some of the marchers had genuine concerns in terms of their employment, housing and safety. These very concerns though are shared with every citizen (and non-citizens) of the UK and driving a wedge between them is part of the class system of rule that suppresses everybody and uses race as a weapon. This is the nature of white supremacy. However real enemy is not migrants, asylum seekers, Muslims or Black people but the bosses that continue to thrive whilst the majority suffer.

5- What impact are these changes having on the lives of migrants already in the UK — from students to care workers to families seeking reunification?

Many migrants are organising with other communities and political activists who are against the wave of racism that governmental policies fan the flames off. Some migrants live in a state of fear in an increasing toxic environment created by the far-right and fed by a pervasive social media. On the streets anybody with a brown skin is fair game to racist and there have been cases of racialised rape and murder that have taken place. Various migrant groups face uncertainty.

Students and international graduates will have shorter post-study work rights and stricter sponsorship conditions. Care workers and social care already face a tougher environment: fewer new routes, restrictions on dependants, and higher barriers. Family migration reunification costs are rising and his will particularly affect migrants in lower-paid jobs, or newly arrived migrants yet to establish higher earnings, making reunification more difficult. Overall the impact on migrants is quite substantial with weaker pathways to settlement and are subject to more scrutiny.

This makes them vulnerable to exploitation by employers and landlords who profit from the reduction in migrant rights imposed by the state. The proposed Reform Party policies, if they can be called such as they are really just Trumpian echoes, would see unheard of numbers of asylum-seekers who have been granted Exception Leave to Remain deported form the UK despite their rights under international and domestic law.

6- With the UK facing labour shortages in key sectors, is this restrictive immigration model sustainable in the long term?

There is much at risk here. The fight against racism has a legacy in the UK and the increasing politicisation of youth because of the genocide in Gaza has made them more keenly aware of injustices at home also. Indeed it is this internationalism that will need to sustain the fight against racism going forward.

In the meantime the forces that use divide and tactics rule and exploit the economic decline of the UK are moving more and more to the centre of power like vultures circling over a dying beast. Playing the ‘race card’ is a sign of desperation as well as a cynical exploitation and the ‘othering’ of the peoples of the Global South in the UK.

The UK’s ageing population, constrained domestic workforce growth plus the removal of overseas labour option means that sectors with high reliance on migration will likely struggle unless domestic substitution is rapid and effective. In the past that substitution has never happened. The political risk is that the government is increasing pandering to right-wing pressure to reduce immigration and that is a performance that may end in tragedy for all of the UK. As has been seen in historically if fascism and racism is not confronted and challenged the results will be horrific. The only solution is organising across communities is to defeat racism, fascism and capitalism.