AI Copyright Infringement and the Unfinished Battle for Creative Rights in Europe

These days, artificial intelligence (AI) has increasingly been integrated into the creative arts. Many generative AI systems are trained

These days, artificial intelligence (AI) has increasingly been integrated into the creative arts. Many generative AI systems are trained on massive datasets. By analyzing various datasets, AI models identify patterns, structures, and relationships within the data and generate new content accordingly. AI models gather training data from multiple sources, including web scraping. While some copyright holders have licensed their data for such usage, most of the content is used by AI models without authorization.

Some people view AI copyright infringement as the beginning of an ownership conflict.

Writers often find phrases that feel oddly recognizable. Musicians notice familiar chord patterns, while artists see reflections of their unique styles. Their own art, polished and repackaged by algorithms, ends up competing against them. Now, lawmakers are attempting to resolve issues that have never been addressed before. Who actually owns something created by an algorithm? And if it borrows too much, is that still creativity or just clever replication?

Behind the Scenes of AI Training

The problem is working out how much tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and its video generator Sora 2, and Google’s Gemini and its video tool Veo3, rely on someone else’s art to come up with their own inventions, and whether using source material from the BBC, for example, constitutes AI copyright infringement of the broadcaster’s rights.

A recent Vermillio investigation showed clear evidence. It highlighted the overlap between creative work and machine learning. The U.S. company provided this. Using what it calls “neural fingerprinting,” Vermillio compared AI-generated videos with copyrighted works. When prompted to create a video resembling Doctor Who, Google’s model produced content that matched 80% of the original fingerprint, while OpenAI’s Sora model scored an 87% match.

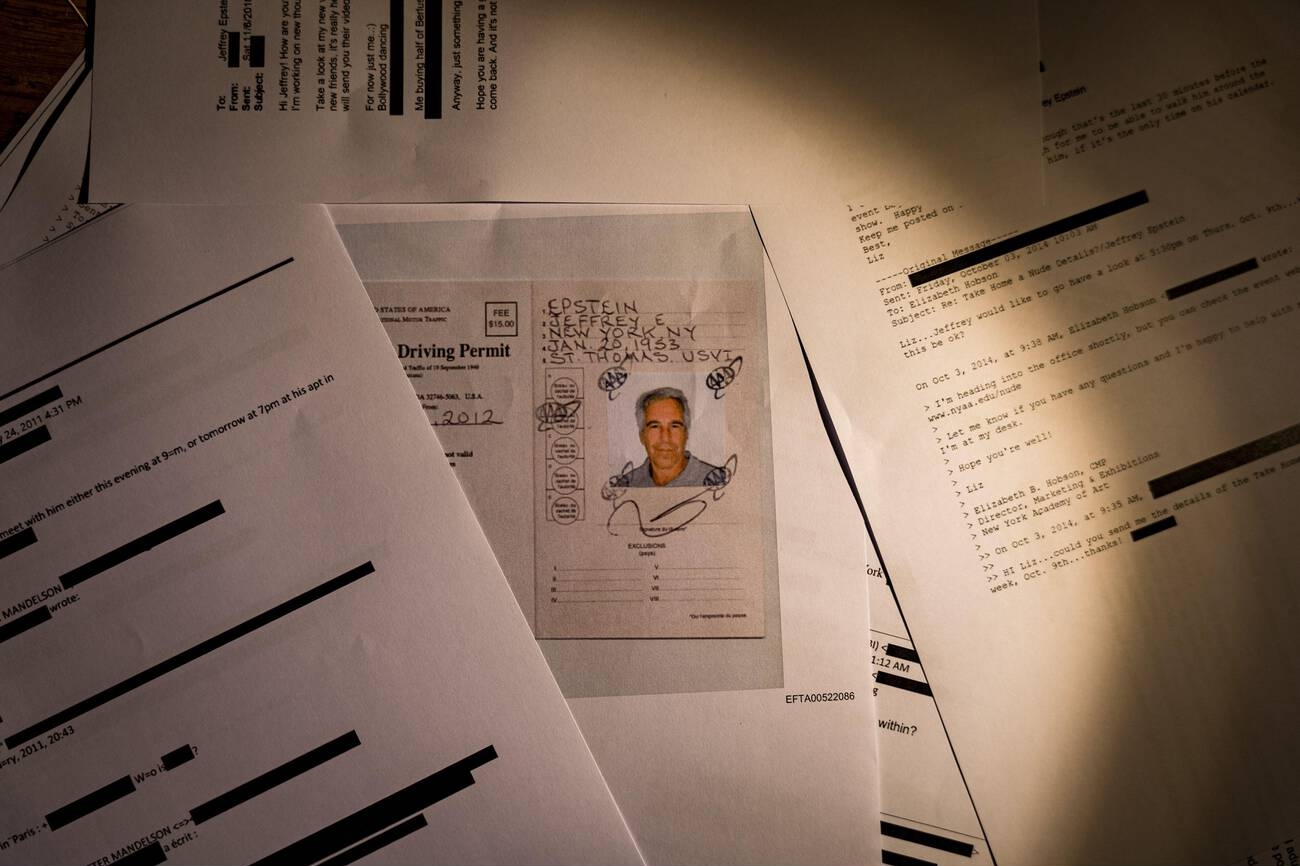

Lawsuits and the Growing Legal Avalanche

The global response has been intense. On May 9, 2025, the United States Copyright Office (USCO) released a 108-page report examining whether the unauthorized use of copyrighted materials to train generative AI systems is a defensible form of fair use.

The report dismissed claims that AI training is comparable to “human learning,” emphasizing that algorithms can create perfect digital copies rather than filtered impressions. Meanwhile, lawsuits continue to pile up. The music publishing industry has presented two years of evidence that AI firms have scraped millions of protected songs to build generative music tools.

The International Confederation of Music Publishers (ICMP) described it as “the largest intellectual property (IP) theft in human history.” In Europe, French publishers have also taken action. Leading publishing houses, represented by associations such as SNE and SGDL, filed a complaint in Paris accusing Meta of using copyrighted books to train its Llama model. According to internal reports, Meta executives allegedly approved the use of pirated content despite warnings from legal advisors.

Europe’s Legal Response: The EU AI Act

In an effort to restore order, the European Union has introduced the EU AI Act, which is set to take effect in August 2025. This sweeping regulation establishes transparency and compliance requirements for so-called General-Purpose AI (GPAI) models—those capable of performing multiple types of tasks using large-scale data. A complementary initiative, the Copyright Code of Conduct (part of the EU’s Code of Practice for GPAI models), provides specific guidance on managing AI-generated copyright infringement material in AI training. It encourages developers to adopt:

A written copyright policy defining internal responsibilities. Mechanisms to detect and respect opt-out signals from creators. Public summaries of training data to allow verification by rights holders. Technical safeguards to prevent the generation of infringing content. Complaint channels for artists and publishers seeking redress. The code is voluntary; however, it serves as an official compliance instrument under Article 53(4) of the EU AI Act.

AI Copyright Infringement and the ”Opt-Out” Paradox

Under the EU’s 2019 Copyright Directive, creators must explicitly reserve their rights to prevent text and data mining (TDM). Many creators are unaware of this clause, while some AI companies ignore opt-out signals altogether.

Dirk Visser, Professor of Intellectual Property Law, spoke to Dutch NOS Radio 1 Journaal and pointed out that if an AI model copies a well-known character, the creator must first demonstrate that their copyright was clearly protected. The system places an unfair burden on artists.

European courts have not yet rendered definitive decisions, leaving artists uncertain about how to protect their work. The recent decisions made by Germany demonstrate the uncertainty surrounding the situation. Courts in Hamburg have allowed the use of copyrighted images for scientific AI training under specific exceptions, but not for commercial projects.

Music, Media, and the Fight for Fair Compensation

The music industry has been among the loudest voices calling for reform to address AI copyright infringement and its impact. ICMP’s report revealed that several AI platforms, including OpenAI’s Jukebox and Google’s Gemini, were trained on music by artists such as The Beatles, Elton John, Madonna, Beyoncé, and many others.

Kathleen Grace of Vermillio, whose company tracks digital IP, argues that transparency benefits everyone: “We can all win if we just take a beat and figure out a way to share and track content. As a result, AI companies would have access to more intriguing data sets, and copyright holders would be encouraged to release more data to them. Instead of giving all the money to five AI companies, there would be this amazing ecosystem.”

The Ethical and Economic Stakes

AI tools run the risk of undervaluing original work when they can mimic human creativity with just a few lines of code. As British filmmaker and policymaker Beeban Kidron remarked, “If Doctor Who and 007 can’t be protected, then what hope for an artist who works on their own, and does not have the resources or expertise to chase down global companies that take their work, without permission and without paying?”

Instead of empowering artists, AI may unintentionally replace them by flooding the market with derivative works that compete directly with their own. AI’s ongoing transformation demands evolving legal frameworks. These frameworks strike a balance between innovation and intellectual property rights. This evolution effectively addresses AI copyright infringement.

A Turning Point for Digital Creativity

The debate on AI copyright infringement centers on equity. The European Commission released the Code of Practice for General-Purpose AI Models on July 10 2025. This release closely aligns with the implementation of key provisions under the EU AI Act, scheduled to commence in August 2025. It strikes a balance between technological advancement and the protection of creators’ rights. Is it possible to advance innovation while eliminating the artists? The EU’s AI Act and its new Code of Conduct for Copyright are early steps toward finding that balance. Whether those efforts succeed will decide not only the future of creative work but also the meaning of art itself.